- ‘AnotherKind’ is a funeral for a piece of theatre which never existed and a celebration of the birth of a new hybrid artwork.

- It draws from Amy Louise Wilson’s Distell National Playwright award-winning script ‘Another Kind of Dying’.

- Due to the pandemic, ‘Another Kind of Dying’ was not able to be staged as a play.

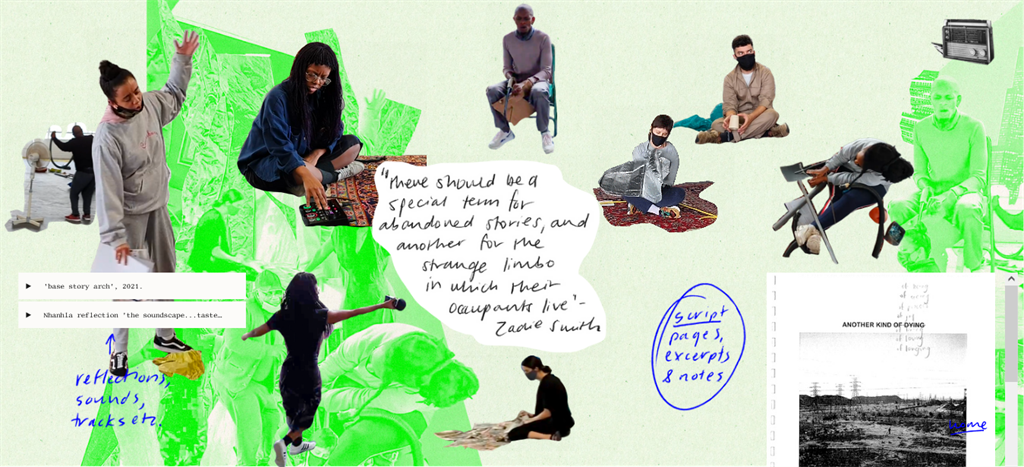

Where do waylaid stories go? For the team behind the planned production of the 2020 script for Another Kind of Dying, they incubate, become an opportunity for reflection, collaboration, and process – a building and breaking apart of a script, and an archive of work. What emerges from this methodology is a hybrid live and digital performance, “a funeral for a piece of theatre which never existed”, and another kind of theatre-making.

Theatre is changing. Evidenced by the kind of work on show at virtual festivals like the NAF, it’s no longer so reliant on a physical space or a traditional stage, for one. But the way theatre is being developed and disseminated is changing, too. In Another Kind, produced by 2020 Distell Playwright winner Amy Louise-Wilson and her dynamic team of collaborators, we are given a piece of theatre that is made with contemporary tools, methodologies, and modes of engagement, delivered through video, performance, sound, imagery, and process.

The script, an early iteration of which was shown and tested at the 2020 vNAF, follows the story of Silumko (played by Aphiwe Livi) from rural Eastern Cape to bustling Johannesburg. It is an enduring story about loss, dreams, breathing and becoming, and it follows a rich South African literary tradition – the tale of a pastoral protagonist who undertakes a journey to the city, changing (and being changed by) the world around him.

Delayed on its way to the stage once again, Another Kind is primarily a response to a need for theatre in an ongoing pandemic, yes, but it is also an interactive, digital repository of a performance on the workshop floor, a long view of the act of storytelling. Text, sound, film, inspiration, conversation, collaboration – all of it is held onto and referred to, neatly and imaginatively housed on a custom webpage-turned-tangible-archive.

Curated by Wilson and web-designed by designed by Francis Burger, the screen is a palimpsest, a scrollable archive housing all of the written and reworked parts and disparate fragments that continue to inform its greater structure. The secondary thoughts, the peripheral and experimental ideas that were pushed aside, but which continue to inform from the margins, are all still held and put to use. Here, words perform, images dance, video works alongside the printed word and music guides the silent act of reading. It is, to borrow from the writer Ivan Vladislavic, an ‘exploded view’ of a performance in progress, broken open to illustrate and investigate the many moving parts that make it whole.

Activating this extraordinary archive are a series of live-streamed desktop performances by Wilson who, from within the neat borders of a notepad app, guides audiences through the interactive page, and along the journey of producing the work. It begins on Woodstock’s Albert Road, where a video shows the team of collaborators making use of everyday materials – poles, paper, plastics packets – to develop a burgeoning chorus, a swelling soundscape. Soundbites add further context, while fragments of the scene – images of the team in action and key items from the story – invite you to engage with them, dragging them across the screen to play with and produce collaborative collages of your own. All the while, Wilson’s words work away like a ghost in the machine, talking you through the contents.

From here, we follow the journey of Silumko in tandem with the journey of the play itself, moving through the tall, yellow grass of Alice on the border of the Eastern Cape to the bristling soundscape of Johannesburg’s Park Station. Collages by Duduetsang Lamola aka blk banaana set the scene, and costume and dreamy film courtesy of Francois Knoetze further immerse us in the unfolding script. As we read the stage directions detailing Silumko springing into action and racing after a bakkie rattling down a dirt road (an image which Wilson reveals appeared to her in a series of dreams), Bongeziwe Mabandla’s ‘Ndokulandela’ plays out from the left of the screen, lending a rhythm and texture to the scene. We journey to Silumko’s aunt’s house in Alex, from the cosmopolitan reaches of Mall of Africa to the ceaseless labour of construction sites and the arresting vignettes that comprise Silumko’s dreamscape.

We do not move in a linear fashion. Time, the ever-present chorus reminds us, is circular. We dip in and out of it, shifting experience and perspective all the while. In a particularly striking scene where Silumko learns of the circumstances of his father’s death, Wilson’s words appear in the word-processor again: “This scene is, for me, the most painful moment to watch… I’m going to close my eyes now. But you watch.”

It is a mournful, clawing scene full of breath and yearning, airless and overwhelming. We wade further into abstraction, deeper into the dreamscape where Silumko asks his friend: “How did you become brave?” (an essential question about freedom, we are told). The scene comes to a close, and Wilson’s words return, guiding us out of it: “Take a deep breath now. I’m taking one, too. Roll your shoulders back and down. I’m going to move us into a place of joy now. High up on a rooftop in Hillbrow. Here is a Silumko we haven’t seen before.”

A recurring motif guides us now, the crackling radio, alive with music. It is the radio that Silumko listened to as a boy, surrounded by his cattle and in the shade of a tree. In the Eastern Cape, powered by batteries his father would bring back from Johannesburg, it would play his mother’s favourite song, Leta Mbulu’s ‘There’s Music in the Air’. Now, on an inner-city rooftop where fabric flutters in the breeze (a beautiful realisation of a dream-sequence we see earlier) it churns out the radio hits of the day and Silumko, the protagonist so weighed down by memory, the burden of history, and the agony of choice, dreams, and identity, begins to dance.

Certainly, theatre is changing. In Another Kind, we are given an idea of where that change can take us, and how the archive, the rich repository of storytelling, methodology, collaboration and more, does not have to remain static. Rather, it can serve as part of the process itself – a relentless pursuit of performance that is always in a state of change, and open to new ideas. A process that is generous, generative, and democratic.

There is so much more to say about a body of work such as this, and the many people that helped build it. But time, although circular, is of the essence and Wilson still has two more desktop performances to share with us. Go and watch them. They are extraordinary.

This article was first published by The Critter. Arts24 has partnered with the National Arts Festival to bring you exciting content before, during and after the 11 day festival.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners