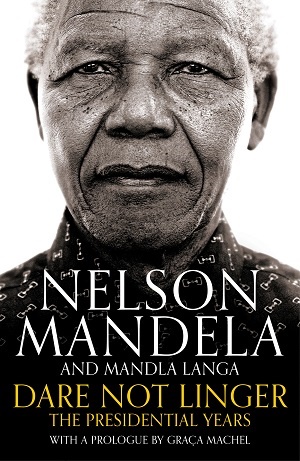

If there was ever an anticipated book to hit the shelves, it is former president Nelson Mandela’s second memoir, Dare not Linger.

The 360-page book, which takes its title from the final passage of A Long Walk to Freedom, draws heavily on the memoir Mandela started writing shortly after his presidency ended. He had written roughly 70 000 words before his strength started to fail him.

It took celebrated South African author Mandla Langa 11 months to complete the book, using Mandela’s original drafts, along with detailed notes that he made as events unfolded.

Released this week by Pan Macmillan, the book comes at a time when revisionists have started to question aspects of Mandela’s legacy, providing a timely opportunity for the man himself to answer his detractors.

Langa is sensitive to this fact and believes the book offers unique insights into Mandela’s thought processes as he navigated the first presidency of democratic South Africa. He is critical of the lens many detractors now use to criticise Mandela.

"I wanted to reflect on the gravitas of the person, without the book becoming a hagiography," he explains during an interview just before the launch of the book this week.

"However, people must have the sincerity to look at the time when things happened and use the lens of the moment, rather than the lens of today. Hindsight is a perfect science."

Reading Dare not Linger is indeed like looking out of a window to the past through the eyes of the man who stood central to the unfolding of a country’s history. It is truly fascinating.

While most of the events the book deals with are public record, Mandela’s private thoughts on them were not – until now.

His strained relationship with former president FW de Klerk and his private frustration with many of De Klerk’s actions comes strongly to the fore. When De Klerk wrote to Mandela to suggest a meeting between the president, IFP leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi, deputy president Thabo Mbeki and himself, to mediate and end to the violence in KwaZulu-Natal, Mandela, who at that stage had had met several times with Buthelezi, could not resist the urge to put him down.

He wrote back: "Rather than suggesting pointless meetings, I would appreciate your input on how to deal with the legacy of the inhumane system of apartheid of which you were one of the architects."

Of course, in public, he reserved his criticism for De Klerk to a large extent. Langa recalls a conversation with Mandela’s widow, Graça Machel, about the relationship. She confirmed that Mandela felt restrained by his own project of reconciliation in what he could say publicly.

"He wanted to build bridges, and he knew that people weren’t leaders for themselves. De Klerk was not just a leader for De Klerk and his family. He was a leader for a whole constituency of the South African reality, as was Buthelezi. His view was that you cannot, by any stretch of the imagination, humiliate a person like that in public, because that would in fact be a humiliation of his supporters. And so he tended in public to be very reconciliatory with people like De Klerk and Buthelezi, but privately he would really read the riot act," Langa says.

This was also one of the reasons he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize jointly with De Klerk.

"At some stage, he did feel it might be an endorsement of the whole history of the National Party. But, in the end, he felt it was also a Nobel Peace Prize for all the people of South Africa, De Klerk included."

Madiba’s characteristic contemplative tone permeates the entire book, which showcases his astute ability to win people over to his cause, his commitment to reconciliation above everything else, and his hands-on approach to matters that required sensitive mediation.

But it also paints a picture of a man who was, in hindsight, perhaps too idealistic about the future, didn’t quite grasp the depth of the economic problems he inherited, and whose plans didn’t make provision for the fact that not everyone involved would operate with intentions as pure as his.

He was further frustrated by an inexperienced government and the unwillingness to participate by those not ready to follow the path of reconciliation.

His approach to governing may have been best described by the late Professor Jakes Gerwel, Mandela’s right hand man, who said:

"Madiba was in some sense inadvisable; he’s got what the Germans call that 'finger-tip feeling'. The old man sometimes makes a political call because he has an intuitive sense for timing."

The book contains many moments that leave one wondering how a different decision might have altered the course of history.

One such a moment was Mandela’s endorsement of Cyril Ramaphosa to be his deputy president, only to be overruled by the ANC and African statesmen like Julius Nyerere and Kenneth Kaunda, with whom Mbeki had already built relationships.

Another was the Sarafina II scandal that occurred under then Health Minister Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma. It was one of the first cases of state corruption that caught everyone’s attention. She offered to resign, but Mandela declined, leading to intimations about a lack of assertiveness to prevent corruption on his watch.

Langa is ambivalent about this.

"It’s not entirely untrue to say that corruption had started during his watch. But it would be placing such an onerous load on one person to expect him or her to have been alive to just about everything that was happening around him.

"He had put in place an infrastructure for a democracy, a good country, imbued with positive values. By the times he handed over the reins, he had done what he was supposed to do."

As then deputy governor of the Reserve Bank, Gill Marcus, is quoted in the book: "So much is expected of us simultaneously that there is no room for sequencing. There is too much to do and we are trying to do it all."

But there would always be too much to do and that, for Langa, is the point.

Some 23 years down the line, the book is perhaps a timely reminder of what could have been. Reading Dare not Linger in today’s context does not come without a feeling of tragedy – sadness about the way it all turned out and how South Africa has in many ways betrayed every ideal Mandela stood for.

"The ANC and the country right now is in a crisis, and he really would’ve lamented the situation. But I would think that Mandela had a sense of history and that history has got ups and downs and is not linear. He would’ve seen this as the extended birth pains of a different dispensation," says Langa.

"Perhaps, if people read the book they’ll realise how possible it was at one stage to be great. And I think that’s the only legacy we can think he left them with.

"People look at Mandela and look at today’s circumstances and do not see that one of his major preoccupations was to create a foundation for a democratic South Africa. Now, it’s up to the ones who are living in that house that has been built to make sure it stands the battering of the elements."

We dare not linger any longer.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners