FW de Klerk's statement that apartheid was not a crime against humanity led to a firestorm and has damaged the former president's legacy, perhaps fatally. Leon Wessels, who served in De Klerk's Cabinet vehemently disagrees with the former president, and says apartheid's crimes are his crimes, writes Pieter du Toit.

"I might not have pulled the trigger on Anton Lubowski, or sent the letter bomb which led to the unspeakable murder of Abram Tiro, but it is for my account," says Leon Wessels, the former minister in FW de Klerk's Cabinet, deputy chairperson of the Constituent Assembly and human rights commissioner.

"You can say, as many do, 'Look, I wasn't in politics then' or 'I wasn't involved in that', and 'Don't be angry at me because I didn't kill him'. It's crap. I was an Afrikaner, I was a nationalist, the whole thing is on me. It is for my account."

Wessels, who served under PW Botha and De Klerk, is now 73 years old. And he has absolute clarity on apartheid, the damage it wreaked and his complicity in it. His convictions are in stark contrast to that of De Klerk, the last apartheid president, who cannot bring himself to fully engage with the sins of the past.

It is early on Thursday morning and we are sitting at the Mugg & Bean coffee shop in the Key West Shopping Centre in Krugersdorp, the town on the far West Rand that he represented as a National Party MP.

As we are talking about the De Klerk furore, reconciliation and apartheid, his phone rings. It is Sello Hatang, the chief executive of the Nelson Mandela Foundation. They discuss the De Klerk matter. Hatang calls Wessels "Tau".

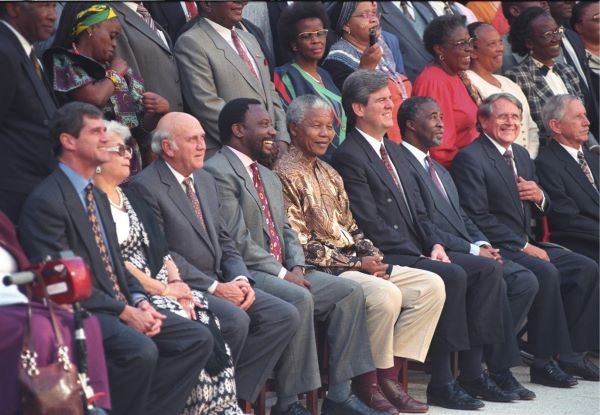

Not sitting at the same table: FW de Klerk and Leon Wessels at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in August 1996. Wessels is not surprised at De Klerk's contention that apartheid was not a crime against humanity. (Gallo Images)

"I wasn't surprised by De Klerk's statements [about apartheid not being a crime against humanity]. But I was surprised by his reaction and his apology and retraction. That isn't De Klerk's style," Wessels explains after his call with Hatang ends.

There are legal arguments to be made about apartheid and whether it is a crime against humanity, he says, and proceeds to walk through various UN resolutions, international conventions and the Rome Statute of 2002.

"Those are all legalistic in nature. But it's a non-debate … it's a non-debate, because that's not what this is all about. This is about morals and emotions. Apartheid was a crime against humanity. And we must look its brutality and crudeness in the eye."

He again refers to Tiro, the leader of the South African Students' Organisation, who was blown up by a letter bomb in 1974. He has become friends with Tiro's nephew, Gao, who has written a recently released biography of his uncle.

"We killed Tiro… I was part of it," he says and explains he is complicit because he was part of the system.

"It took me a very long time to understand the system. And a long time to understand how brutal and immoral it was. And the reason why I didn't do anything was because I was afraid … afraid of a black majority government.

"And that fear only really subsided one day in a swimming pool with Joe Slovo at a bosberaad when we really got talking about a majority government. And suddenly, you're sitting at a negotiating table with Nelson Mandela … a terrorist!"

But Afrikaner tribalism also played a role in his fears, Wessels says. "There was the fear of going against your own people, of being excommunicated by them."

And that seems to be De Klerk's greatest mental block. If he completely disavows apartheid as a crime against humanity, he will repudiate his father, Jan, who served in Hendrik Verwoerd's Cabinet. And Wessels believes he simply cannot do it.

"De Klerk's biggest fear is to be branded as having repudiated his father. End of story. He cannot bring himself to aggressively condemn the old [apartheid] policies.

"I heard him say in meetings: 'But they were good people'. His uncle, Hans [JG] Strijdom [a prime minister in the 1950s], his father Jan … he grew up in those circles. He grew up sheltered and isolated. He was protected from the brutality of apartheid. He grew up in ministerial homes, he sat at dinner tables with them, he was protected as a young backbencher, and before he knew it, he was a Cabinet minister.

"He never saw the cruelties of the Group Areas Act and Mixed Marriages Act…"

Apartheid's legacies are still with us

It is winter 2019, and Wessels is taking me around Krugersdorp. We talk about apartheid and its legacy. And how we cannot escape it. We are driving on the R563, the Sterkfontein Road, with the suburbs of Munsieville to the left and Dan Pienaarville to the right. The Group Areas Act designated the former for blacks and the latter for whites.

Wessels says the spatial divides that apartheid created is one of its starkest leftovers. "So, when we decided on how our towns were going to look, we commanded: 'The whites can have the town … then the blacks can stay there and the Indians and coloureds there … all separate. It was madness."

Those arrangements, separate group areas, still exist almost everywhere.

We drove into Munsieville, past matchbox houses and the church where Winnie Madikizela-Mandela famously made her necklacing speech ("With our boxes of matches and our necklaces we will liberate this country…"), through the white suburb with its large properties and golf club, past the centre of town where a mosque used to be (before it was moved) and onto Azaadville, way out of town, where the Indians were dumped.

And past the Paardekraal Monument, where the white supremacist Eugene Terre'Blanche was famously disposed of his dignity one night in the backseat of a car.

Wessels (left) with Nelson Mandela at the multiparty negotiations in the early 1990s. They had a warm and close relationship, with Mandela once urging Wessels to have the Human Rights Commission take the government to court. 'Take them on,' he told Wessels. (Gallo Images)

Wessels explained the intricacies of group areas, influx control, security measures. He spoke about being a National Party MP for Krugersdorp, how he had to persuade and convince the "conservatives" to vote for him, and how he had to battle the racist white right.

"I was called a k**** boetie during political meetings in the Town Hall. I had to 'debate' Clive Derby-Lewis, the Conservative Party's candidate," he blurted out in what seemed to simultaneously be a smirk of disgust and a howl of surprise.

Thirty, 35 years ago that was Wessels' life, defending the National Party against the rising tide of the white right. At the time the government of PW Botha was being lambasted as being too soft on the "terrorists".

"Liberals" like Wessels became a target during raucous and often violent political meetings in the Krugersdorp Town Hall.

"I grew so tired of the sterility of that type of politics … of white politics, while many of my compatriots in town, blacks, had no say in the country," he said on the way to Kagiso, the black suburb on the outskirts of the city.

We were on our way to Basadi Pele (Women leading from the front), a project that his wife, Tersia, has run since 1993, the year before democracy.

Thousands of children have gone through the foundation's doors, with pre-school and primary school care and education (and food!) provided on-site by qualified teachers. And next door is the Thusang Morwalo (We lighten the load) Advice Centre, a legal advice clinic, that will be a decade old next year.

Tersia has qualified as a paralegal to help and Wessels does shifts there, dispensing free advice about matters like maintenance and inheritance.

Inside Basadi Pele, the smell of coffee and maize meal filled the air. It was school holidays, and the only children that were there were in the creche. In another classroom, four teachers were discussing a course they had just completed.

De Klerk at the State of the Nation Address on February 13. (Bertram Malgas, News24)

"We're very proud of what we've achieved. And it hasn't been easy. We're dependent on donations and grants," Tersia says.

Three former pupils came by while we were drinking tea and coffee with the teachers and staff. One was studying law, another is a cricket development coach with the provincial board, and another has his own business, repairing cars. Wessels jokes with the female law student that she must represent him once she earns her degree. She laughs shyly.

On the way back to Key West, Wessels told of a march in Kagiso, during the turbulent late 1980s. He was then deputy minister of law and order (under the notorious Adriaan Vlok). ANC and Inkatha supporters clashed and shots were fired, with ANC supporters being killed. The police did nothing to stop the deaths.

"I called the station commander and demanded to know why they did nothing. I was livid. He said they didn't see anything! But the march went straight past the police station! What do you mean you didn't see anything? I demanded. He just shrugged," Wessels recalls.

During apartheid, nobody ever knew anything.

Born a nationalist but a midwife at the birth of the Constitution

Wessels was born in 1946, two years before the National Party rose to power. His father was a policeman, and Wessels was to later also join its ranks after graduating from police college. He studied law at the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education, graduating in 1972.

He rose quickly in the ranks of the powerful Transvaal National Party, was elected member of the Transvaal Executive Council in 1974, became a member of the party's provincial leadership and MP for Krugersdorp in 1977. His party and government leader was the impregnable John Vorster.

Wessels was passed over for a Cabinet position by PW Botha in 1986 (many thought he would be elevated to a ministerial position then) and was instead appointed deputy minister of law and order in 1988.

De Klerk shifted him to foreign affairs (under Pik Botha) a year later, before being appointed minister of planning, provincial affairs and national housing in 1991 and finally minister of local government, national housing and manpower in 1992.

But Wessels' main preoccupation in the early 1990s was not government, it was negotiations.

Starting out as one of the National Party's lead negotiators, he became one of the outspoken progressive voices in the Cabinet, alongside Roelf Meyer and Dawie de Villiers.

"There was no other way, and there wasn't any other option but the right option. Some of the proposals that were made in the Cabinet and by the conservatives, men like Tertius Delport, were never going to work. Rotating Presidencies, an upper House of Parliament with veto rights … if we were going to have a democracy it had to be done right," he said during the long conversation driving around Krugersdorp in the winter of 2019.

Former National Party ministers in 2010, from the left, Dawie de Villiers, Wessels, De Klerk, Pik Botha and Roelf Meyer. (Media24 Archives)

Wessels and Meyer worked closely together during Codesa I and II, and the subsequent multiparty negotiations. Both men tried to convince the De Klerk Cabinet - and often the then-president himself - that unqualified, universal franchise was the only option left. And they explained the final agreement reached with the ANC's Cyril Ramaphosa to a group of stunned ministers one morning during an emergency Cabinet meeting in Pretoria.

Democracy, Wessels says, gave him space to breathe and the chance to escape the stifling sterility of whites only and especially Afrikaner politics. He served as Ramaphosa's deputy in chairing the Constituent Assembly - the body that wrote the final Constitution - and, along with Meyer, persuaded an intransigent De Klerk to support the passage of this democracy's foundational document.

When the Constitution was signed into law, Wessels resigned as an MP for the National Party, leaving Parliament after 19 years. There was nothing left for him in politics. He proceeded to appear in the Constitutional Court as an advocate - a highlight, he says - and went on to serve as human rights commissioner for a decade. He earned his doctorate in law and was appointed a visiting professor. Today, he serves on the boards of the Constitutional Hill Trust and Council for the Advancement of the South African Constitution (Casac).

Next to De Klerk at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Wessels sat next to De Klerk at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1996 and listened as the former head of state delivered his apology for apartheid before Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu.

The now defunct South African Press Association reported on August 21 of that year that De Klerk "apologised on Wednesday for the 'immeasurable pain and suffering' caused by the NP's former policies, but denied his government had ever sanctioned the assassination, murder or torture of opponents".

He went on to say: "I should like to express my deepest sympathy with all those on all sides who suffered during the conflict. I and many other leading figures have already publicly apologised for the pain and suffering caused by the former policies of the National Party. This was accepted and publicly acknowledged by … Archbishop Tutu. I reiterate these apologies today."

During his second appearance at the TRC, in May the following year, he said: "I apologise in my capacity as leader of the NP to the millions who suffered wrenching disruption of forced removals; who suffered the shame of being arrested for pass law offences; who over the decades suffered the indignities and humiliation of racial discrimination."

The NP's second submission to the TRC, which De Klerk presented that May, rejected the idea that apartheid was a crime against humanity. He then argued that it could not be compared to "the Nazi Holocaust, the rule of Russian dictator Josef Stalin, China's 'Great Leap Forward' or the recent genocide in Rwanda".

SAPA reported that De Klerk, in the submission, argued: "Without wishing to detract from the humiliation, hardship and disruption caused by apartheid policies, they are not in any way comparable with these situations. The International Convention that had purported to declare apartheid to be a crime against humanity, had been little more than a mobilisation exercise by the African National Congress and its totalitarian and Third World supporters in the UN General Assembly."Wessels, seated between Mandela and Thabo Mbeki, then deputy president, shortly after the final Constitution was adopted in May 1996. (Media24 Archives)

Journalist Max du Preez, who despised De Klerk's government, said he wanted someone to speak on behalf of his (white) tribe, that he was anxious that someone should reach out to black South Africans and apologise unreservedly. On behalf of himself, his ancestors and his children. And De Klerk was perfectly placed.

But he disappointed. For Du Preez, it was a wasted moment. De Klerk should have asked for forgiveness and acceptance. He did not. The moment was gone.

"His speech was void of any emotion, of any sense of momentousness. They were the carefully considered words of a clever politician and a lawyer. It was a clinical apology for something others had done, even though they had 'meant well' when they started apartheid. My heart sank," Du Preez wrote.

De Klerk's guarded apology was roundly criticised. Tutu, who called the initial atonement a "handsome apology", said De Klerk "spoiled it by virtually qualifying it out of existence".

His deputy, Alex Boraine, was equally disappointed: "Once again, the contradictions emerged: the security forces carried out their evil deeds on the clear understanding that they were obeying their political masters. But De Klerk would have none of that. He stressed over and over again that he hadn't known about illegal actions and refused to accept responsibility for them."

Eugene de Kock, who headed the murderous Vlakplaas police unit, rejected De Klerk's statements. In his memoir, A Long Night's Damage, he writes that De Klerk "sticks in my throat".

"Not because I can prove, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that he ordered the death of X or cross-border raid Y. Not even because of his holier-than-thou attitude that is discernible in the evidence he gave before the TRC on behalf of the National Party.

"It is because, in that evidence, he simply did not have the courage to declare: 'Yes, we at the top levels condoned what was being done on our behalf by the security forces. What's more, we instructed that it should be implemented. Or, if we did not actually give instructions, we turned a blind eye. We didn't move heaven and earth to stop the ghastliness. Therefore, let the foot soldiers be excused. We who were at the top should take the pain. We who were at the top are sorry'."

'I cannot say 'I did not know' … we didn't want to know'

Wessels appeared in front of the TRC in October 1997. By then he had escaped from the National Party and was free to speak his mind. He had re-qualified as an advocate and was about to start his tenure at the SA Human Rights Commission.

He told Tutu and the TRC: "I do not believe that the political defence of 'I did not know' is available to me, because in many respects I believe I did not want to know. In my own way, I had my suspicions of things that had caused discomfort in official circles, but because I did not have the facts to substantiate my suspicions or I had lacked the courage to shout from the rooftops, I have to confess that I only whispered in the corridors.

Wessels on Thursday, talking about apartheid and reconciliation. Apartheid crimes, he says, 'are for my account'. (Pieter du Toit)

"That, I believe, is the accusation that many will level at us.

"We simply did not, and I did not, confront the reports of injustices head-on. It may be blunt, but I have to say it. Since the days of the Biko tragedy, right up to the days of hostel activities, hostel atrocities in the late 1980s, the National Party did not have an inquisitive mindset. The National Party did not have an enquiring mind about these matters."

De Klerk elicits mixed feelings in Wessels. He was never close to the former president; he did not support him in the party's leadership contest, and he has always known him to be deeply conservative.

During our various conversations over the years - about apartheid, nationalism, the transition and the dangers of the new white right - Wessels has never outright denounced or condemned the 84-year old Nobel Peace Prize winner. But he has also never been reverential about the man who unbanned the ANC and released Nelson Mandela.

There is neither warmth and admiration, nor antagonism and hostility in his voice when he speaks of De Klerk. Rather, disaffection and neutrality.

"The difference between De Klerk and me is that he mourns for Afrikanerdom. But I want to be a bridge builder, I want to be a diplomat. I try to gather like-minded people together."

Also read in this week's Friday Briefing:

FW de Klerk never had any moral intention, and he left us behind as white kansvatters, by Antjie Krog

No shame, no remorse: How Afrikaners are dealing with their apartheid past, writes Lindie Koorts

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners