Former South African politician and diplomat Denis Worrall would need a somewhat different public record for history to judge him as a hero of struggle on the ground in South Africa. That accolade belonged to people like imprisoned Nelson Mandela and banned Beyers Naude.

Yet Worrall made his mark in the struggle of the mind. This ultimately helped lead to greater enlightenment in the cause of averting a full-scale civil war. Working broadly in his own pool, at first rather cautiously, influencing mainly white opinion but later showing bursts of real courage, he was to play a role in a country lurching to democracy in 1994.

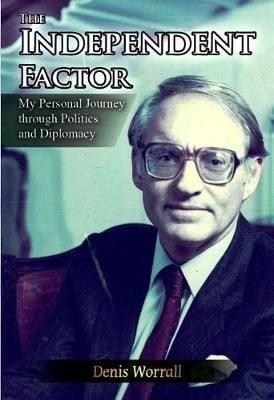

Worrall's book, titled The Independent Factor, goes back to his relatively modest origins, growing up in white society, attending a parallel medium Afrikaans/English school in Bellville, Cape Town. He had enviable status: head boy, senior cadet officer, first team cricket and rugby and one-mile running champion – though dux eluded him. He admits being "undistinguished" academically, except for debating.

Yet he became a PhD, politician, ambassador (to Australia then UK), columnist and editor (of the serious journal New Nation), and an advocate at the Cape bar, etcetera. His was a household name. His pot-pourri earlier life included being a Nationalist Senator and MP ("clearly on the left wing", he stresses). Later he was to play a key role on PW Botha's discredited advisory President's Council that outrageously locked black Africans out of its constitutional proposals.

He gives useful descriptions of Botha's celebrated non-Rubicon crossing in a speech that sank the rand, the Coventry 4 arms-sanction-busting case in which Pretoria's solemn word over bail to a UK court was broken, Margaret Thatcher's near death in the Brighton hotel bomb explosion, the reform-minded but stillborn "Natal Indaba" regional KZN plan, which he liked. And so on.

Worrall in time became an eloquent ally, among others, in showing how history can be clawed back from the cliff. His efforts backed up those of prescient verligtes in Afrikanerdom, such as Schalk Pienaar and Ton Vosloo, leaders among the enlightened at Cape-based Nasionale Pers. They saw early on the apartheid game was up, and tried to do, or say, something. They kept carefully within their traditional cultural context, but duly earned PW Botha's tongue-lashings. Such brave forces are too often overlooked these days, as we chart our new history.

This book of short chapters is only 217 pages, unlike memoir tomes around in recent years. He writes with a fluency greater than that of many practiced academics.

His background was hardly indicative of the Worrall to come. He had moved, cautiously and defensively, with the times in relatively safe verligte company. We, his often-critical contemporaries, rubbed our eyes to see him transmogrified from a Vorster-era National Party caucus member and later ambassador, vaulting right across the chasm ultimately, on two fronts: resigning his London ambassadorship for the hustings, and joining the triumvirate leading the Democratic Party (now Alliance) into pivotal support for the Mandela-De Klerk deal. Zach de Beer and Wynand Malan were the other two. It was a close shave for SA (and Worrall) to get to that point despite the past.

Pushing in the verligte scrum, Worrall was always light on his feet, like a good rugby flank. He broke away at the right moment and scored the above two sensational tries. His detractors, hopefully somewhat diminished by his memoirs, can never take such transforming moments away from him.

All this is pretty agile mobility for one public life, considering that politicians of all hues can get more hidebound and cautious as they grow older, and more frustrated with the elusive "art of the impossible", something still very necessary in SA. Worrall seemed more liberal as he grew older.

This agility was viewed cynically by some, but I think a modest round of applause is more apt. It redeems an at times dubious political background that, frankly, liberals, social democrats, black nationalists and the far left once tended to suspect, especially in our worst of days.

In his writing, the seriousness is broken by a touch of the risque. He relates how, exploring Times Square in New York when, just out of university and unable to get into his booked Taft Hotel, he was "approached by two attractive young ladies". One "adroitly put a hand where it pleases most, and said: 'Honey: why so saft (sic)?'" He offers only: "Just at that moment, a cab pulled up, the back door opened and a gentleman invited them to join him". One assumes, for the young lad from Africa visiting the concrete jungle, it was fright and flight not delight.

Worrall left UCT with a master's degree in 1959, having been taught by noted professors in political studies, etc. He also studied law. He taught and researched abroad, including in the US (where he earned his PhD at Cornell), and Nigeria (Ibadan University) where, apart from constitutional pursuits, he was – the only white running, followed by a horde of blacks – the fastest miler at the Nigerian universities' athletics championship.

That didn't harm his later career. Former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo loudly lauded his athletics feat, when Obasanjo (co-chair) and members of the Commonwealth Eminent Persons group met Worrall and others in the 1980s. (The EPG was sabotaged by defence minister Magnus Malan's bombs landing on three southern African Commonwealth capitals to wreck negotiations with SA.)

Later, Worrall's was to be a voice in play in the Codesa negotiations in the early 1990s.

His book relies somewhat on quotations from his and others' speeches and comments, with a tendency to include more favourable remarks about himself – a human temptation. Yet there is enough objective observation and personal experience for sustained reader interest – even a glance back at tidy-minded, Worrall-friendly Margaret Thatcher, warning her celebrating party workers not to spill orange juice on the carpet.

The book's text is clear and well crafted, making for a read that is not hard labour. An exception is over-much detail towards the end concerning an admittedly needle election in Helderberg, Cape, in the 1987 general election, in which ex-ambassador Worrall was gloriously involved on a liberal-inclined ticket, losing by only 39 votes against a shocked PW Botha ministerial hack now happily lost in history. Remember Chris Heunis?

The value of people like Worrall writing up their lives is not just in informing and entertaining, but in contextualising events from their own personal experience. He shows a sure grasp of the political and diplomatic process. He might have given us a bit more of his deepest thoughts and fears on his political odyssey, on the presumably successful business life he built up, and our future as a country, as he sees it.

Such insights are of value not only for historians and analysts of the past, but anyone interested in the dynamics that nearly destroyed a country. All South Africans can benefit from the insights. As we crawl crab-like towards a more just destiny, we are the more able to avoid repeat disasters. Our institutions, our society and our political parties are under renewed pressure as the "defining year" of 2019 begins, and major decisions lie ahead as the election campaign gets under way.

The age-old question whether to remain in a movement and fight for justice from inside or step outside to make a moral stand at personal risk – manifest in some decisions Worrall made – stares many in the face at this moment. Hearing first-hand about Worrall's dilemmas and struggles highlights the value of some whites being able, looking back one day, to feel a little more comfortable about their role as part of the previously cosseted classes. And hopefully to say about a country corrupted by race, then money: "Never again."

SA will be rough in the future. But we've seen worse. Read apartheid, e.g. a thousand blacks a day arrested under pass laws. So let's keep a balanced sense of direction on the promising Ramaphosa national road, now with us. Worrall's book is one driver in that direction.

- Heard was Editor of the Cape Times, 1971-87, received the Golden Pen of Freedom from the world newspaper publishers' body in 1986 for publishing an illegal interview with banned ANC leader in exile, Oliver Tambo, and a former special adviser in the ANC Presidency and government.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners