By this point my research into my mother's particular home really had all come to a dead end, and now the long long story of invasion and dispossession in the area was simply drowning out the private urgencies of our specific narrative. It was time to let it go.

And then I sang the lullaby with Joseph.

It was Sazi Dlamini's idea. A musician and ethnomusicologist from Durban, he had said I should ask Joseph. That he would know it, if anyone did.

'Joseph?'

'Shabalala.'

'Of course. Ladysmith Black Mambazo.'

When I called Sazi at a friend's suggestion we somehow found ourselves talking about the Amdokwe chant, which he also remembered from listening to Radio Bantu in the sixties. We were the same age, and the sound of it was inscribed in both our memories, inseparable from the call of that particular bird.

'It's ivukuthu,' he said. 'The dove.'

'They used to play it on Radio Bantu when I was a child.'

'Yes!' he remembered. 'It was the children's programme. Nine thirty in the morning.'

He started making the dove's call, hooting through his hands into the phone.

'Sounds really do take you right back into the memory,' I said.

'Yes, it's very direct.'

So Sazi knew Amdokwe, but he couldn't translate my mother's lullaby. All I knew of the meaning was that somehow the song concluded with the sound of cannons on the Ladysmith mountain, guns from Alan Smallie's war. It was frightening, yes, but seemed to make a kind of sense. For do we not find some of the most beautiful lullabies unsettling, even as we are held in the arms of our mother's song?

I got Joseph Shabalala's number from his agent, and told him the story. I said I was looking for the words of the lullaby my mother used to sing me, that it was the one she herself had had as a child in Natal, that she was now very old and remembered only the earliest things, and that I wanted to be able to sing it with her again, and to understand the words. I explained that I felt shy to sing it to him because the song had been repeated so often that its meaning was probably lost.

'Yes, repetition. That is lullaby.' His voice was gentle. 'Hold on,' he said, 'I want to take a pen. I'm very serious about this.'

Tentatively, I sang the words I knew. I was in Cape Town and he was in Durban. He listened and asked me to sing it again. The second time he began to join in with a harmony.

'I know it!' he said, and sang the song once more, working out the words. 'It's from the early times. They would sing it at a wedding. It's an apology. It says we are not fighting, we were not quarrelling. It's a calling to forgive one another.'

'Wow.'

'When you come with this, you are extending things. I'm just back from America where we have been recording lullabies for three months. I think this is the time for raising up everything which is falling down. Watering the seeds.'

We sang it again together, harmonising.

'It's saying, dear lady, we are not fighting.'

'Would it be for the man or the lady to sing?'

'It's for everybody.'

'And the cannons, mbayimbayi?'

'They remind us of the day when we love one another. We say that to love one another . . . We say I love you like something that shoots me.'

'So you mean that the cannon, which is about wars and violence, the sound of those cannons on Mbulwana during the Siege of Ladysmith . . . You are saying that in the song the cannon has become something to do with love?'

'Yes! When we say this, kwaduma mbayimbayi, we say this when we love one another. The love is so powerful, it is like a thundering. I've used that part about mbayimbayi,' he said, and sang his version in a warm tenor voice.

'But now you came with something,' he went on generously. 'We must be sure I have your number and your name.'

'Joseph, this is wonderful. This song has been with me all my life, my mother's lullaby, but I never really understood it.'

'Yes, it is wonderful. Call me anytime.'

'And the song, it was for weddings, but it could also be a lullaby?'

'Wedding, lullaby, it fits everywhere.'

'Thank you, Joseph. Now I can sing it with her.'

It was, as he put it, a song that was singing in the early time. We sang it again together over the telephone:

Sasingaxabene

Wemsheli wam

Kwaduma mbayimbayi

Phansi kwembulwane.

Afterwards, I called my friend Abner Nyamende at UCT, and together we came up with this translation:

We had not quarrelled

My beloved

The cannon was thundering

Below Mbulwana.

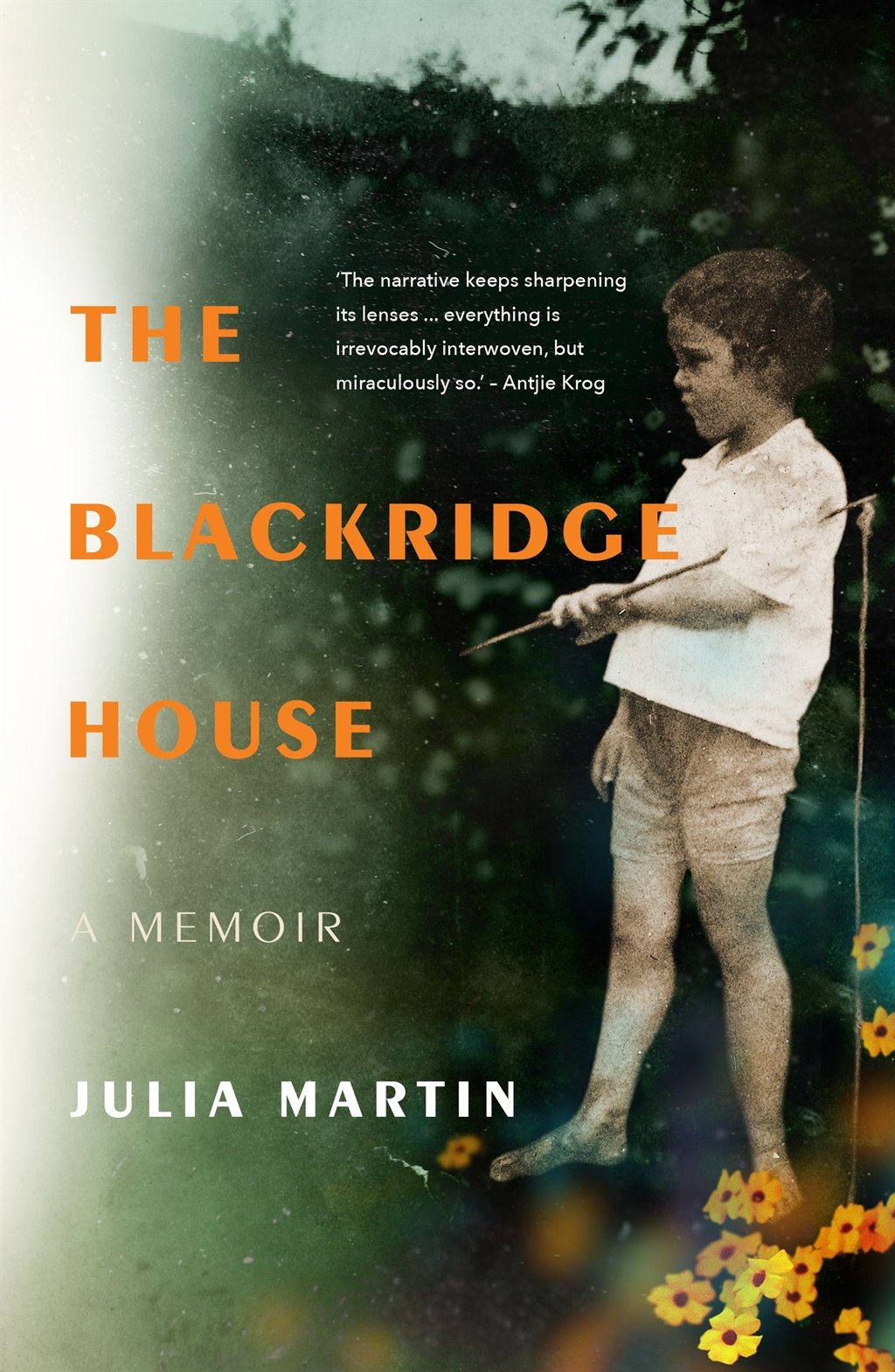

* This is an extract taken from The Blackridge House by Julia Martin, published by Jonathan Ball Publishers. It is the story of Martin's mother's dementia and a daughter's quest to find the house her mother grew up in.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners