"On the night my father was killed, I was three years and eight months old. Dorothy was just weeks away from her tenth birthday, while my 26-year-old mother was seven months pregnant with my younger sister, Tumani."

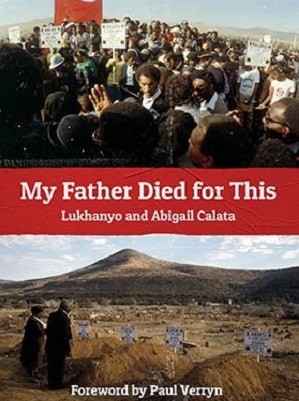

So writes Lukhanyo Calata in his book (co-written with his wife Abigail), My Father Died For This.

The names Calata and Cradock loom large over the history of our country's struggle against, and liberation from, racism and white minority rule.

From Lukhanyo's grandfather Canon James Calata – a leading member of the ANC, who became secretary general of the movement in 1936 – to his father Fort, and his rock of a mother, Nomonde.

For many South Africans, Lukhanyo's brave stand against Hlaudi Motsoeneng's mad machinations at the SABC may have been the first time they heard about the Calata family.

But this is a family whose DNA is part of the struggle against apartheid.

Canon Calata and his grandson Fort had a huge impact, both nationally and on the local Cradock political, social and cultural landscape.

But it is the tragic story of Lukhanyo's dad, Fort Calata, that is central to this powerful and important book.

Turning point

The brutal murders of the Cradock Four in 1985 by the apartheid police were a turning point in the struggle against the white racist regime.

For the three-year-old Lukhanyo Calata, it was a much more personal turning point. It was the day he lost his dad.

Lukhanyo says he has no memories of his father, apart from the day he was buried.

The funeral of Calata, Matthew Goniwe, Sparrow Mkhonto and Sicelo Mhlauli on July 20, 1985, in Cradock was massive. Despite a ban being placed on people travelling to the funeral, and many being turned away at roadblocks, an estimated 60 000 people from across the country made their way to the small Eastern Cape town.

Cradock was the town where I, like Fort and Lukhanyo, grew up. Of course, we didn't exactly grow up in the same place. I lived in the white town, while they lived in the impoverished black township of iLingelihle.

This little township would become a shining example to others, particularly rural ones, around the country of how to organise and mobilise against the apartheid regime at a local level.

The year that Fort and his comrades were murdered was the same year that I left Cradock and started my studies at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, about two hours' drive away.

Personally, I was thrilled to get out of Cradock. I had not particularly enjoyed my high school years there. Bullies, in the form of teachers and fellow pupils, made life pretty hellish.

And then, there was the racism.

A racist little town

I had grown up in a relatively liberal household. My parents voted PFP and disapproved of blatant racism. So, it was a slight shock to my system when I was confronted with words like "kaffir" and "hotnot" on a daily basis. Of course, these slurs were never aimed at me. They were reserved for black people, often hurled by white children at their black elders.

I didn't escape the slurs, but they were mainly based on that old Anglo-Boer divide. I was called "rooinek", "soutpiel" and "Engelsman" more often than by my name. But these insults, while they could sting, were never aimed at undermining and denying my humanity. They were never spat out with quite the same venom and hatred.

Perhaps, the one exception was the slur aimed at me when my fellow pupils realised that I (in my own naïve way, at the time) did not use those racist words and even thought that apartheid was not a very nice thing. "Kaffirboetie!" This word was snarled at me. Basically, I was being called a traitor to my "race", but that still didn't mean I lost any of the privileges of my "race".

I had heard the name Goniwe at school. It was always accompanied by words like "troublemaker", "opstoker", "communist", and of course that old nutmeg, that racists inevitably hauled out when confronted with realities or arguments with which they could not deal: "kaffir".

Around 1984, my father, who had come to Cradock as a Baptist minister, returned to his original career choice of chartered accountancy after the small church quite literally died out. He went to work for the black town council in iLingelihle.

Liberation movement's flags unfurled

I remember him coming home one day and saying he had met this really impressive community leader from the UDF, who was also a teacher. His name was Matthew Goniwe. My dad, while mainly liberal and anti-racist in his views, was not a fan of the UDF or ANC, but I could tell that the encounter had shifted his thinking somewhat.

Anyway, I digress. I didn't attend the funeral in Cradock (truthfully, I was a bit scared to return to a town where many of my school "mates" had joined the police – not because they had to, but because they wanted to fight the "swart gevaar"). I still regret not going.

But when some of my student comrades, who did attend, returned with photos and stories of the incredible day (this was long before our instant social media world of today), it dawned on us that something fundamental had changed in our country.

Speakers included the reverends Alan Boesak and Beyers Naude. Two massive flags of the ANC and SACP (both banned) were unfurled and proudly held aloft. The materials had been bought days before and a local seamstress roped in to sew them together.

Local Cradock activist Moppo Mene recalls how they transported the flags into the stadium where the funeral was to be held. Four MK cadres, armed with AK-47s, put them in a bakkie and took them through the roadblocks into the stadium. Although they were terrified that they would be stopped, Mene says, "police and soldiers opened up and just like that we passed through".

Mene and his comrades were, however, detained and severely tortured after the funeral as the security police tried to find out who was responsible for those "terrorist" flags.

A crime against humanity

The apartheid government also knew that things had changed that day. Within hours of the funeral, President PW Botha declared a State of Emergency (mainly in the Eastern Cape), under which thousands of people were detained, tortured, killed, or simply disappeared.

Alan Boesak had this to say to Lukhanyo about the impact of his father's (and his comrades') life and death.

"It was of a brutality that was in many ways unique, and that is why apartheid was officially declared a crime against humanity.

"But we need to remember it was not a crime against humanity in general. It was a crime against our people. It was a crime against our leaders; it was a crime against our children – that is how we need to remember it."

Lukhanyo and his family have been involved in a long, painful battle to get justice for the murder of Fort and his comrades. They have hit one brick wall after another – first under the apartheid regime, which murdered him, and now from our democratic government, for whom he fought.

We have recently seen some belated justice (or at least answers) of sorts in the Ahmed Timol case. This now has to be extended to the Calata and many other families who lost loved ones at the hands of a criminal, racist regime.

Many fathers (and mothers, daughters and sons) died for this.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners