Prologue

In the middle of an October night in 2012, alongside a road that ran through bush on the outskirts of Mfuleni township on the Cape Flats, a 22-year-old albino man called Rowan du Preez lay on the sand with his face to the sky, naked, burnt, and crying out for help. The remains of a tyre smouldered nearby, the only light in the dark verge of the dunes. He was eventually found by two police officers from Blue Downs station.

Some 18 months later these police officers gave testimony in the Cape Town High Court about that night.

'We then stopped the vehicle, M'Lord,' Constable Raul Barnardo said, 'as we heard screaming coming from the bushes outside.' He and his colleague Captain Lorraine Kock left their police car and walked in the direction of the man's screams. They found an 'unknown albino male' who was 'completely naked and severely burnt'. Barnardo also noted bruises on his body, and dark burn marks around his groin and on his feet. 'What's your name?' he asked.

'The victim replied to me wildly that "My name..." that "I am Rowan du Preez".'

He then gave Barnardo his address.

'M'Lord, then I asked the victim what has happened to him. The victim replied to me saying: "I was taken from my house by Angy and her husband, who stays nearby me."' Rowan told him that 'Angy and her husband' had thrown him into a white Toyota Quantum. '"They drove me to Blueberry Hill. They then assaulted me and they put a tyre and tube around my body. They then set it alight and then they left me."'

I had been introduced to Angy Peter's story a few months before. While intrigued, I was unsure of the wisdom of trying to make sense of it. In the months leading up to the trial, Angy told me she had little idea what argument the state was intending to prosecute.

It was only when I first heard Raoul Barnardo tell this story that I knew that I had to write about the death of Rowan du Preez, and the trial of Angy Peter. When Barnardo took the stand, I realised what it meant for three police officers to testify, and, if Angy was telling the truth, each tell a blatant, elaborate lie.

Chapter One

If there was one reason, above all others, that made it hard to believe Angy Peter, it was that I could not reconcile all the ways the world reacted to her. Full-figured and short, with a face that was heart-shaped and apple-cheeked, she was most famous for her sharp tongue.

Upset, she looked at the world imperiously from high cheekbones; relaxed, she would often break into a low, laid-back chuckle. Angy was not short for 'Angela', was never spelled with an 'ie', and scanned on a page it easily read 'Angry'. Often I would be asked, 'How's that Angry Peter story coming along?' Or, 'So did that Angry woman go to jail?' She was self-possessed until the moment she lost her temper, understood morality in black and white, and believed this was a good thing. Some people soon looked up to her, and others instantly disliked her. The people she was most likely to rile – and do not doubt the reaction was immediately mutual – are those we call 'figures of authority'.

Friends – colleagues, comrades – recounted how she had once won a month's free gym membership in a weightlifting competition, had started a cre`che when she saw how the women in her neighbourhood struggled for childcare, and adopted abandoned children and raised them as her own.

Her husband would tell you they could never be on time. On the streets of their neighbourhood Angy couldn't take more than a few steps without someone greeting her, waylaying her with jokes or parrying a jibe. He would tell you people were always knocking on their door, in the hope that she could help.

But then there were other neighbours who said they wouldn't put it past her to commit a crime. She was a stubborn person. She wouldn't 'mind your face' to tell you what she thought. She was a wayene nkani, reckless with words, like someone straight out of Pollsmoor Prison. And when it came to Rowan du Preez – well, she'd held a snake in her lap, and it had bitten her, and then she'd become angry.

I met Angy in December 2013. It was four months before her trial would start, and three before the commission of inquiry into policing in Khayelitsha began, a commission she had been closely involved in instigating. It was the hottest month of a hot and dry summer. I was living in Johannesburg but I had come down to visit my family for Christmas and tagged on an interview with Angy while I was in Cape Town. I took the N2 to Khayelitsha and, not having driven that route in many years, I was constantly checking my phone to make sure I had not missed the Spine Road turn-off; I seemed to have travelled so far.

Rowan du Preez, the man she was accused of murdering, had known her well. Over two years he had regularly joined activist meetings that Angy and Isaac, her husband, held in their own home. They had become, in the parlance of Cape Town's activist NGOs, comrades. But in 2012 they had fallen out badly, and in view of the whole neighbourhood.

Then, on a Sunday morning in October, Angy Peter and Isaac Mbadu were arrested in the adjacent township of Khayelitsha for Rowan's kidnapping, assault and murder. The state would claim at the bail hearing that they had gone to Khayelitsha to flee justice after committing an act of vengeance. In turn, Angy Peter's not-guilty plea stated, 'Killing or hurting [Rowan] was the last thing I wanted. The very real probability exists that the charges against me have been fabricated by policemen.'

I was looking for a story to tell, a stitch that gathered all the dilemmas, contradictions and conflicts of my society together – which I could then unpick, and neatly explain. Angy and I had a mutual friend who had introduced us. They were once comrades, and a few weeks earlier he'd said to me: 'I just came back from Cape Town and the craziest things have been happening to a friend of mine.'

Angy had been involved in activist work that took the rise of vigilante attacks in the townships of Cape Town as the symptom of systemic problems with the justice system, problems which could, her organisation argued, be addressed. Then she was accused of committing a vigilante murder herself, and arrested and charged by the same system she was trying to reform.

At the safe house where Angy and Isaac were living, I felt embarrassed when Angy answered the door. She was made up with rouged cheeks as if, reasonably, expecting me to have brought a photographer. But I was not yet sure I even wanted to write about her case. I was wary about wading into something where the lead characters were activists, where the pull to exonerate 'the good guys' would be strong.

During that interview, Angy and I talked mostly about her activist work. It was obviously what she was most proud of, and, she argued, what had led to her arrest. We sat on a cracked pink leatherette sofa, while Angy's infant son, Alex, crawled around our feet and over her lap. On the TV display case were photographs of her three daughters. Angy's phone rang several times. 'It's the mother of a thug,' she explained. Angy had been taken off the criminal justice work by her NGO, but these mothers still had her number and called her when their sons were in trouble. She used the word 'thug' as if it were a neutral term, the way you'd say someone had brown eyes or green.

When it got to Rowan's murder she could tell me little about the case against her. I pressed. She looked at me confused, almost hurt. She wasn't involved. Her body language said, How would I know exactly what had happened to him?

Yet she said that at her bail hearing the state had mentioned something about eyewitnesses to the assault, and some kind of statement that Rowan himself had made.

A few months later, in the gallery at Angy's trial, it soon became clear this wasn't a case where a conviction might turn on a detail remembered falsely, or a false identification of someone who looked vaguely similar to the true culprit, or the biased interpretation of forensic evidence. This was a case where both sides were accusing the other of wholescale fabrication. Someone was lying. In fact, in either scenario, several people were lying but it was not clear who, or what their motives could be.

Almost everyone I talked to about the case found one side instantly believable. In lefty, liberal circles people hardly bothered to hear the details before declaring that Angy had surely been framed. But anyone who'd worked with the police or the courts, or who lived in places where vigilante violence was rife, didn't blink at the thought she was guilty. 'All my clients say they're innocent,' said one advocate who specialised in criminal law. 'And how would the police even have done it?'

She was clearly guilty, she was clearly innocent. A mother of four had committed a brutal murder for the sake of a television set; an innocent woman had been framed by the police because she had campaigned for better policing. The paradox of these two certainties entrapped me, soon obsessed me, and I spent years trying to arrive at the same state of conviction.

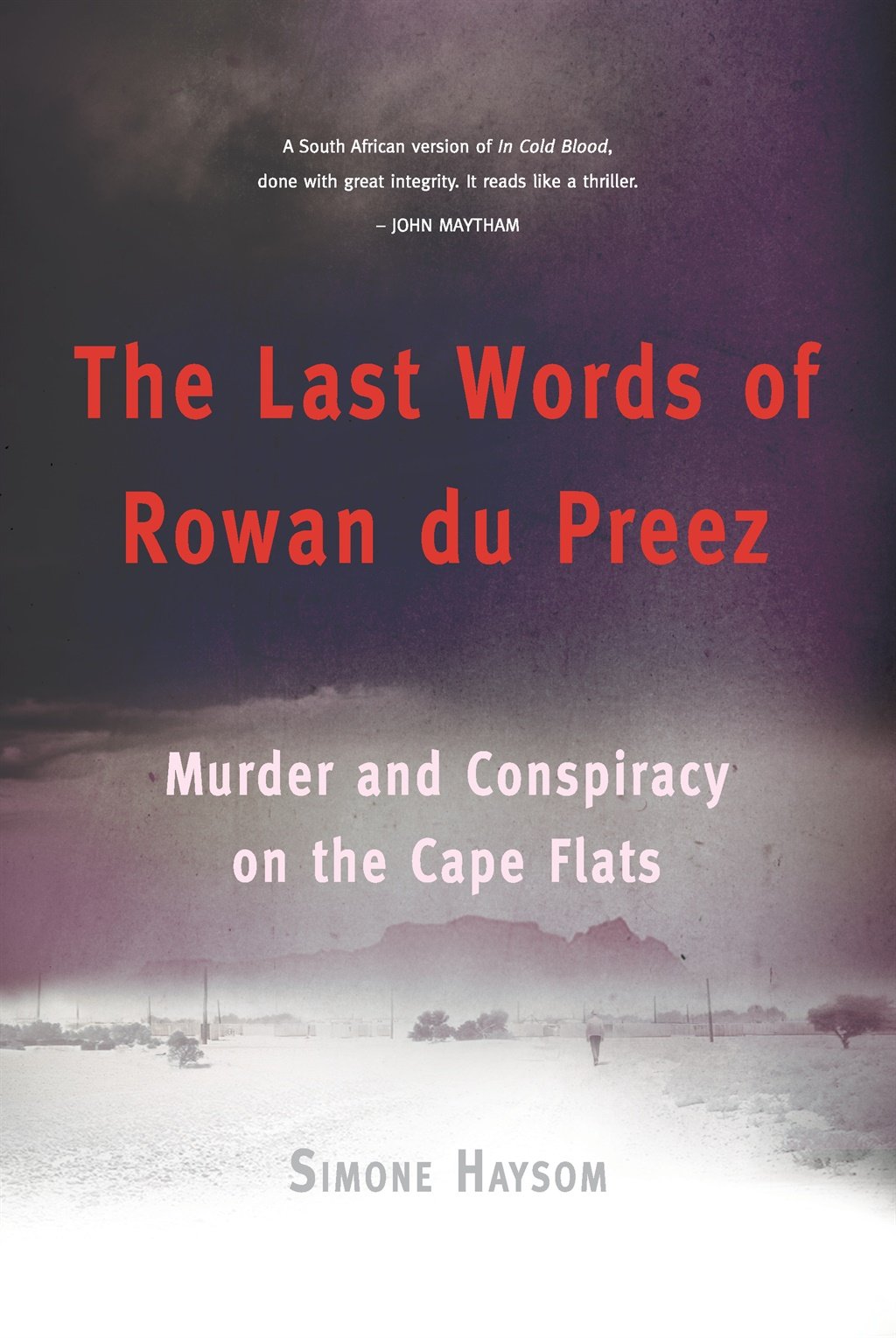

* This extract was taken from The Last Words of Rowan du Preez, published by Jonathan Ball Publishers.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners