Winnie Madikizela-Mandela died as this book was near completion. She was laid to rest amid an outpouring of grief from and respect among millions of South Africans, especially the poor and dispossessed, who revered her for her resistance to apartheid rule and for her sufferings, in prison and internal exile, under the National Party government.

Cyril Ramaphosa, who less than seven weeks before her death had become South Africa's fifth post-apartheid President, led the tributes. "Even at the darkest moments of our struggle for liberation, Mam' Winnie was an abiding symbol of the desire of our people to be free," he said at her graveside. "In the midst of repression, she was a voice of defiance and resistance. In the face of exploitation, she was a champion of justice and equality."

Archbishop Desmond Tutu said: "Her courageous defiance was deeply inspirational to me and to generations of activists. She refused to be bowed by the imprisonment of her husband, the perpetual harassment of her family by security forces, detentions, bannings and banishments."

Mandla Mandela, Nelson's grandson, said: "A rose has been plucked from our garden of heroes. Mam' Winnie has been a shining sun‚ a guiding star‚ an immovable mountain‚ a mother to generations of freedom-fighters; one who has rallied together young and old‚ rural and urban‚ men and women."

But even amid the emotion and tears of Mrs Mandela's farewell, more cautious voices were surfacing. "We must accept that Winnie Mandela was both a heroine and a villain," wrote publisher and commentator Palesa Morudu. Recalling the UDF's 16 February 1989 "outrage" at Mrs Mandela's complicity in the abduction of Stompie Moeketsi, Morudu continued: "The problem with portraying individuals who made a contribution as 'struggle royalty' and lavishing them with such praise is that they begin to believe it. And like all royalty they end up acting as if they are the law, and the peasants be damned.265

"May she [Madikizela-Mandela] rest in peace. Let us celebrate the glory of her legacy – and condemn its horrors."

City Press editor-in-chief Mondli Makhanya triggered a Twitter storm of abuse when he wrote that something went "horribly wrong" when Mrs Mandela was exiled to Brandfort in the 1980s. "It was this period that seems to have irreversibly turned her into the wayward individual she became, a waywardness that many are so dangerously in denial about," said Makhanya.

"She played to the militant gallery … [But] she was just an ordinary human being whose heart was hardened by suffering and whose soul was numbed by torture. We should not elevate her to the status of a role model who we should emulate. If we aim to be contributors to a better nation, we should not try to be the damaged goods that came back from Brandfort."

Several people over the years had urged me, in the interests of "real justice", to conclude this book by arguing for a retrial of Mrs Mandela in connection with the deaths of Stompie Moeketsi and others. They argued that the truth was so seriously abused by the old courts that justice was not done. They also criticised the Truth and Reconciliation Commission for not having lobbied more intensively for a new trial, as it was entitled to do, after it concluded that her alibi was a lie.

It was, however, never the purpose of my exploration for this book to campaign for a new trial. Rather, the motive was to try to tease out the buried, hidden facts, after I had stumbled in this case – and in my reporting elsewhere – on stories in which the truth, to quote Oscar Wilde, was rarely pure and never simple.

Secondly, frankly and pragmatically, such an exercise would have been as futile an exercise as spitting on a red-hot iron, a waste of time and energy. For a whole cat's cradle of legal and political reasons, a retrial was simply never going to happen. Mrs Mandela, who unjustly saw the interior of prison cells in apartheid South Africa, would never have been imprisoned again and she will remain a "struggle heroine" to many people for generations to come.

****

Many horrific stories were told to Archbishop Tutu and his commissioners during the hearings of the TRC's investigations into the activities of Mrs Mandela and her Football Club.

I was particularly moved on day one by the testimony of a young Soweto girl, Phumlile Dlamini, who had become pregnant by one of Winnie Mandela's drivers, Johannes "Shakes'' Tau. Phumlile said Tau was Winnie's lover, and that he had confided to her that Mrs Mandela used to "come to him in the middle of the night and go under the blanket with him". Tau warned Phumlile that if Mrs Mandela found out about their relationship, Phumlile could be in trouble. Phumlile's brother Thole had earlier been shot dead by the Football Club on Mrs Mandela's order, the hearing was told.

Phumlile described to Archbishop Tutu and the TRC commissioners how Mrs Mandela was so jealous of her relationship with Shakes Tau that she ordered that she be kidnapped and beaten. "I was in love with Shakes," Phumlile told the commissioners. "Someone told Winnie. My mother pleaded with Winnie, 'Please do not kill my child.' But Winnie personally said [to her Football Club members], 'Guys, see what you are going to do with this one because she doesn't want to speak the truth.'"

Phumlile continued: "Winnie herself started assaulting me with klaps [slaps] and fists all around my body, and I was three months pregnant at the time by Shakes. I was wearing my maternity dress. It was blue and white. Then they all started assaulting me and kicking me in accordance with Winnie's instructions and I think this continued for about five hours. I was bleeding through my nose as well as my mouth."

Phumlile denied an assertion by Mrs Mandela's lawyer at the TRC, Ishmael Semenya, that the story was a figment of her imagination. "She [Winnie] knows deep down inside of her that I am not telling lies," said Phumlile. "I have absolutely no reason to come here and sit and waffle."

Phumlile Dlamini's baby son, named Tsepo, was born prematurely with brain damage. Phumlile said she had never reported the assault by Mrs Mandela to the police because "I was scared of having my house burned down. I [once] loved Winnie, but after I was assaulted and after my brother's death I changed my views completely. I didn't want to hear that she was the Mother of the Nation."

The TRC officially concluded that "Ms Phumlile Dlamini was a credible witness and that her allegation of assault at the hands of Ms Madikizela-Mandela and other members of the MUFC [Mandela United Football Club] is consistent with the modus operandi of other incidents of assault that have taken place at the Mandela house … On more than one occasion she and members of the MUFC were responsible for assaulting Ms Dlamini." Inexplicably, however, the TRC commissioners did not insist that Mrs Mandela be questioned, let alone charged, in relation to the assault upon Phumlile.

****

Researching the subsequent fate of the "small" players in the Mandela United Football Club history, I went in search of Phumlile Dlamini in Soweto to try to find out what subsequently had happened to her and her son. There seemed to have been no follow-up by the South African media to her story.

Several days after I began my quest I talked to a former Football Club member who told me Phumlile had died of Aids in that era when Thabo Mbeki, successor to Nelson Mandela as President, came under the influence of a small group of American scientists who denied the scientific consensus that Aids was caused by an HIV viral infection which could be combated by sophisticated drugs. My informant did not know what had happened to Phumlile's son after her death.

I badly wanted to find Kenny Kgase, beaten by Mrs Mandela alongside Stompie but emotionally destroyed in pitiless cross-examination by George Bizos, so that I could ask him how he was faring. Kgase, I was told, disappeared to somewhere in East Africa after Mrs Mandela's conviction. But no one, including the Reverend Paul Verryn who had been close to Kgase and concerned about him, has since heard from him. No one seems to know whether he is dead or alive.

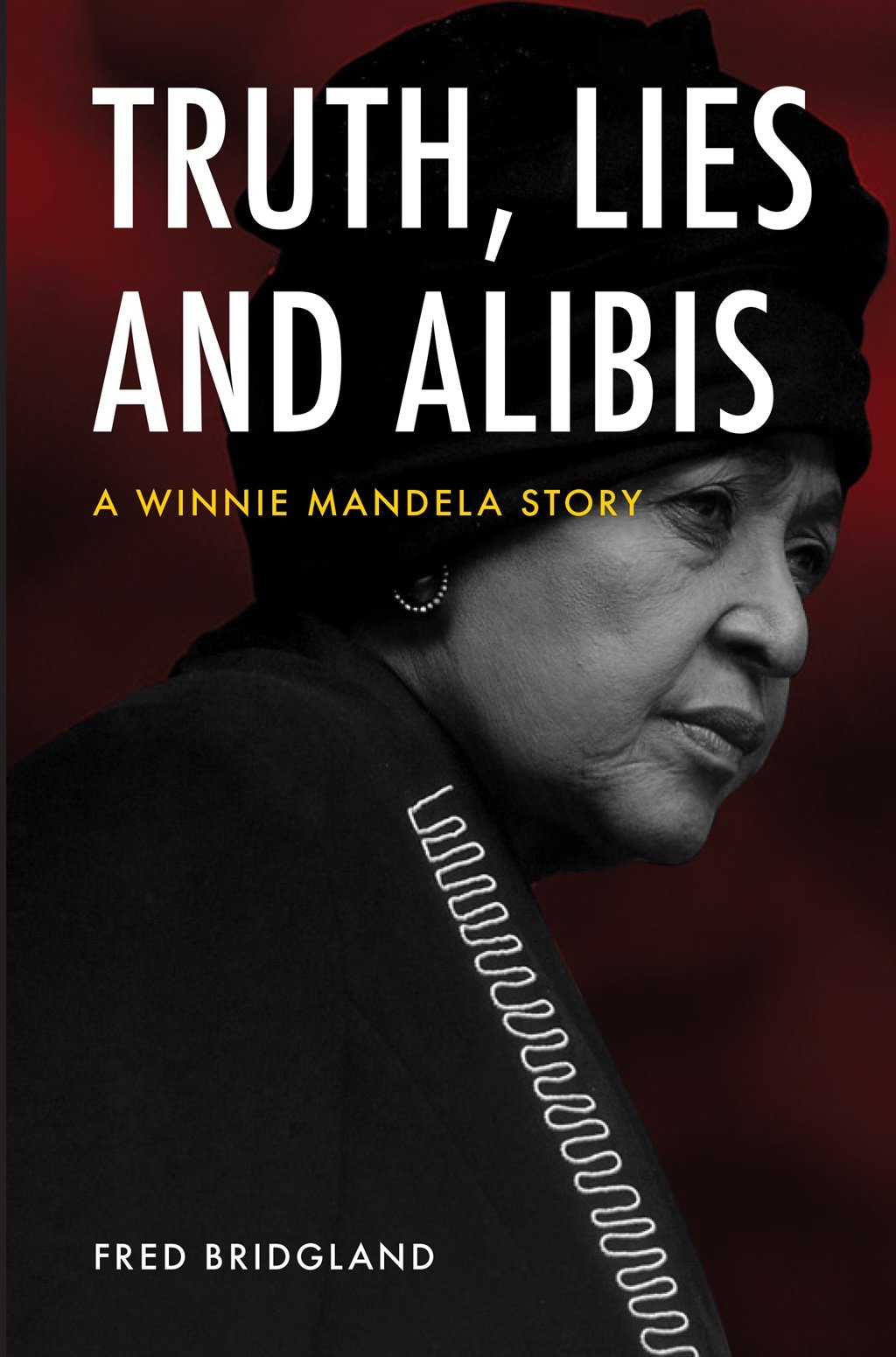

* This extract was taken from Truth, Lies and Alibies by Fred Brigland, published by Tafelberg and retailing for R265.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners