This article forms part of the archives of Business Insider South Africa, which was published as a partnership between News24 and Insider Inc between 2018 and 2023.

- Scientists think humans evolved scalp hair to minimise heat gain from solar radiation and reduce the need to sweat.

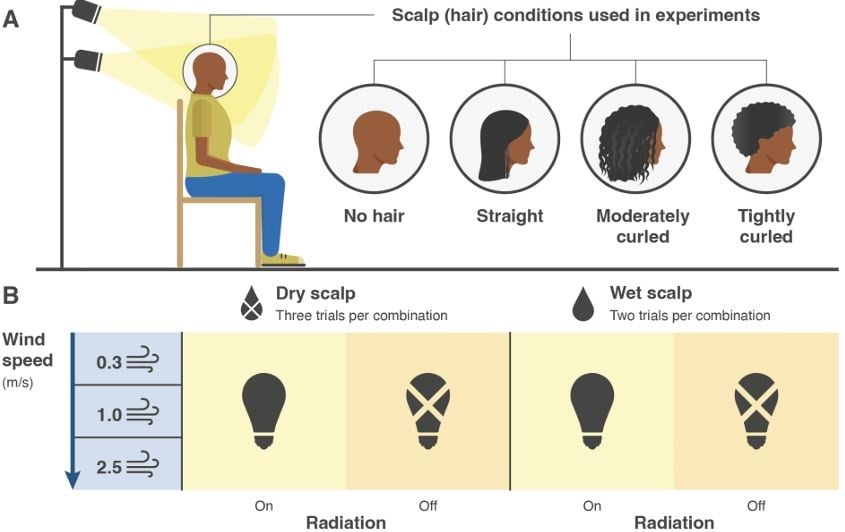

- The first experiments to test this theory involved measuring the temperature of a manikin wearing different black wigs.

- All the wigs helped, but tightly curled hair performed best, probably because it doesn’t lie flat and allows the scalp to ‘breathe’.

The tightly curled hair found in many African populations, but which is not common elsewhere, comes out on top in the first study of which hair type provides the best protection from solar heat.

Scientists say tightly curled hair is far from the “wool” it is sometimes equated with, because it does not trap heat close to the body like an insulation layer.

“Instead, its advantage is in protecting against excessive heat exposure from solar radiation while still allowing heat loss,” says a team led by Tina Lasisi, an anthropologist at Penn State University in the US.

The chiskop, or shaven head, preferred by some African men means the scalp sweats copiously so that evaporation compensates for the absence of hair’s cooling effect, the study finds.

Tightly curled hair is a uniquely human characteristic, and its ubiquity in Africa in spit of the continent’s wide genetic diversity means a study of its role was long overdue, Lasisi says in a paper posted on the preprint server bioRxiv.

As humanity’s ancestors started to walk on two feet and develop larger brains, scalp hair may have struck the best balance between maximising heat loss across the whole body and minimising heat gain directly over the brain.

“Sweating works in tandem with a seemingly hairless body to create a highly effective cooling system, but this physiological response is not without cost,” says Lasisi.

“Sweating increases the need for fluid replacement and thus safe water, and can lead to dehydration. Less costly adaptations for keeping cool may have offered significant benefits.

“Tightly curled hair may provide an additional reduction in heat influx beyond the capacity of typically straight mammalian hair.”

Lasisi’s team put wigs made of human hair from China on a thermal manikin and conducted their experiments – including a set with a bald head – in a wind tunnel with heat lamps simulating the sun. They simulated sweat by soaking the manikin’s cotton skin with water.

“In general, the highest solar heat gain was experienced under the nude condition, and straight hair, moderately curled hair and tightly curled hair showed decreasing heat gain in that order,” says the paper.

When the scientists looked at which model was the most efficient at achieving heat balance – where incoming solar heat is exactly matched by heat losses from the scalp – they found tightly curled hair needed only minimal sweat at low wind speeds and none when the breeze picked up. But the nude scalp needed the most sweat to achieve heat balance.

“Our most striking observation is the clear pattern of decreased solar heat gain with increased hair curl,” says Lasisi.

“The closest parallel in the animal literature is the decrease in solar heat gain with increased depth of a fur coat. Tightly curled human hair does not lie flat on the scalp and therefore increases the distance between the surface of the hair and the surface of the scalp.”

The African conditions in which humans evolved had high solar radiation and scarce sources of drinking water, says Lasisi, and “in these circumstances, evolution would have favoured adaptations for water conservation. A plausible scenario could be the evolution of tightly curled hair that insulated against heat and reduced water loss while also extending how long individuals could engage in strenuous physical activity before needing a drink.”

Now Lasisi says more experiments are needed to see how significant hair is in regulating the temperature of the whole body.

“The head represents a small fraction of the body’s total surface area,” she says. “We must investigate whether hair offers enough protection to significantly affect body-wide thermoregulation or whether the local protection it offers to direct brain heating is sufficient.”

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners